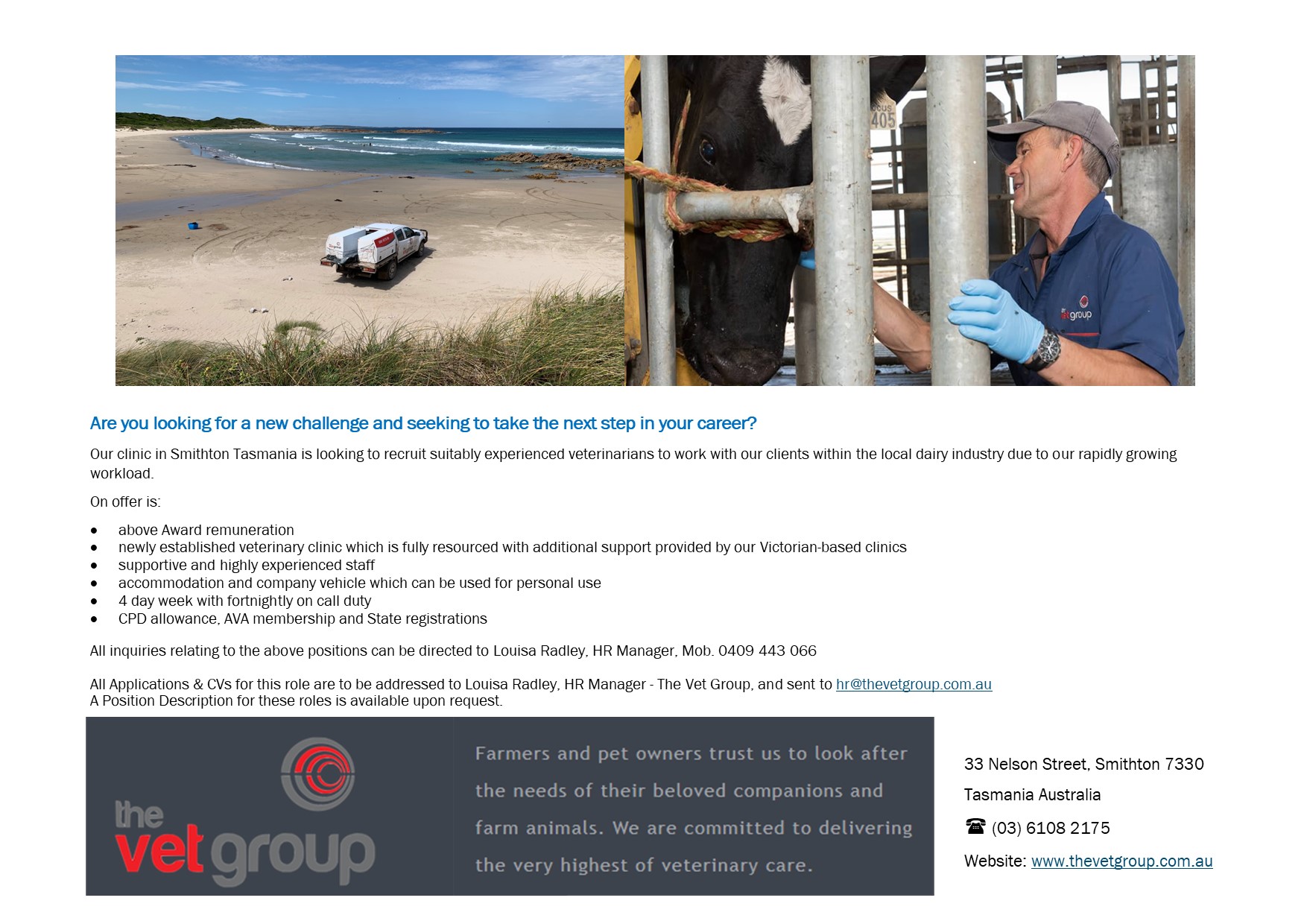

Mastitis in cows can be caused by many different bacteria. But knowing which bacteria is causing a problem on farm helps focus efforts to prevent new infections. The photo below is of two milk cultures that were recently done at one of our clinics. The agar plates we use have three different types of agar: different bacteria grow on different thirds and in different colours. The two cultures don’t look much different at first glance. But after following a simple interpretation chart, we know that one is Staph aureus and the other is Enterococcus.

Milk cultures identify the likely source and help focus preventative actions

We generally class mastitis bacteria into two broad categories. Environmental bacteria live in mud, faeces, water and dirt and contaminate cows’ udders and teats between milking times. Cow-associated bacteria live on the skin of the teat and in the milk within the udder. These bacteria are spread from cow to cow during milking time.

So from knowing which bacteria were present in these two milk cultures our advice might be:

- Staph aureus: lives on the skin of teats, especially in cuts and cracks. Assess teat condition of the herd and ensure post-milking teat spray is the correct concentration and covers the whole barrel of all teats.

- Enterococcus: found in cow manure. Maintain teat health and minimise contamination of teats and udders: ensure cows are standing in the hour after milkings, especially in muddy/wet conditions.

Milk cultures can help decide treatment and culling protocols for a farm

Some bacteria respond well to antibiotic treatment, while other are innately resistant to most of the antibiotics available. With regards to the two milk cultures above: we know that Staph aureus is really good at hiding away in the cow’s udder and resisting the immune system. Hence infections with Staph aureus are less likely to cure during lactation and intramammary antibiotic at drying off can be an important part of treating infected cows.

Because these agar plates have a much faster turnaround than sending milk samples away to the lab, more and more farms (particularly in North America) are setting them up and using the results to inform treatment decisions. For example, a cow no bacterial growth might not be treated: their immune system has already killed off the invading bacteria. This selective antibiotic treatment reduces treatment costs because

a) less antibiotics are used and

b) milk is withheld from the vat for shorter periods of time.

Is selective treatment of clinical mastitis something that will be economical for you? The best way to find out is to know what’s on your farm. For example, if you sampled 10 cases of clinical mastitis and 7 were no growths then selective treatment might be something to consider. On the other hand, if 7 were Enterococcus then there may be no benefit in setting up a milk culture system.

Numbers matter!

When looking at what’s causing mastitis on a herd level, the more milk samples the better. Consider if these two samples were from the one farm. Is it a cow-associated problem or is it environmental? It’s hard to say! But if there were 7 Enterococcus samples and only 1 Staph aureus sample we would be confident to say that there’s a problem with Enterococcus and focus efforts on preventing environmental mastitis.

For more information about these in-house milk cultures or if you have any questions about your farm’s milk quality please talk to one of our veterinarians. Instructions on how to take a milk sample are available here. Pre-prepared packs of milk sample containers, alcohol wipes and these instructions are available at our clinics.