As the cold weather of winter starts to set in – it’s a good time to think about how calves can be affected by cooler temperatures.

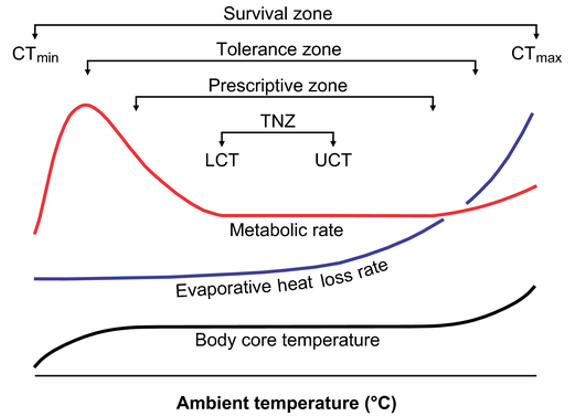

All animals have what is called a “thermoneutral zone” (TNZ). As shown in the picture below, it is the temperature range where animals don’t need to expend energy to maintain their body temperature. Above an upper critical temperature (UCT) animals sweat, drool and pant to keep cool. They will also eat less and move less to reduce the amount of heat they produce. Below a lower critical temperature (LCT), animals put energy into generating body heat. They also change their behaviour: seeking shelter or crowding up with other animals.

The values of the upper and lower critical temperatures depend on the type, breed and age of animal. The lower critical temperature for calves is:

- 0-3 weeks of age = 15-20ºC

- >3 weeks of age =10ºC

How do calves generate heat?

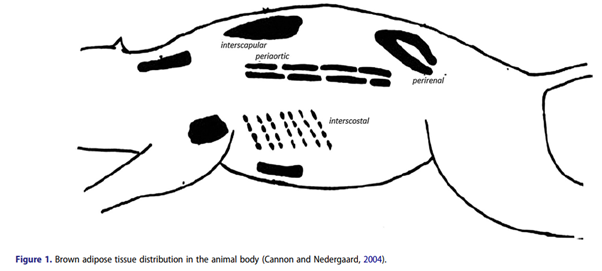

There are two ways that calves generate heat. The first is brown adipose tissue. This is a special type of fat in newborn calves. It is found between the shoulder blades and covering the heart, kidneys and major blood vessels (see picture below).

Brown adipose tissue contains vast amounts of mitochondria. Mitochondria power the cells of the body by producing the molecule ATP. When calves are cold the brown fat is metabolised and, instead of generating ATP, the mitochondria let the energy go as heat

The second way calves generate heat is the shivering reflex. This is the rapid contraction and relaxation of muscles which creates warmth (apparently shivering expends as much energy as riding a bicycle!)

Cold: what does it cost?

A farmer recently asked “what’s the cost when a calf is cold?” That is, can you put a monetary or production value on it?

Going by the National Research Council’s calculations for daily weight gain, at 5ºC below their LCT, calves use the amount of energy to maintain their body temperature that could have instead gone towards about 100g of weight gain. So for example, at 15ºC a 2 week-old calf might put on 400g in a day rather than 480g.

At 10ºC below the LCT, calves sacrifice about 200g-worth of potential body weight in order to generate heat, and at 15ºC below the LCT they use up 300g-worth. Depending on environmental conditions, body weight and what they’re being fed, calves may even lose weight in order to stay warm

When talking about weight gain in calves, a target that many references quote is for calves to double their birth weight by 8 weeks of age. This is because, all other things being equal, these animals should make 750–800 L more milk in their first lactation. Another study that looked at the combined result of several different studies recommended keeping daily growth rates above 500g per day to maximise first lactation milk production. If calves are cold – how likely are they to meet this weight gain target?

How to help calves stay warm…

- Providing shelter from wind and rain: rain, mud and faeces reduce the insulation value of the calf’s hair coat, so it’s important to keep them dry. Wind chill makes calves colder than the ambient temperature. Use shade mesh or plastic as quick fixes for blocking the wind in calf pens. For calves out in the paddock, stacked hay bales make an easy windbreak.

- Cosy bedding: thick bedding will reduce the transfer of heat from the calf to the ground. If calves are able to nestle into the bedding it can trap a layer of warm air – straw is generally considered the best bedding for this. When nesting, instead of expending energy to maintain body heat, calves are able maintain their immune system which in turn reduces the risk of disease.

- Calf coats: again these can trap a layer of warm air around the calf and help them stay warmer. It’s important that coats are put on dry calves. While it may be impractical to give every calf a coat, having some available for newborn calves, sick calves or smaller calves (like Jerseys) will be helpful.

Rumination: stoke the fire!

Older calves are more tolerant of colder temperatures because they have started ruminating. Imagine the rumen as a fire and the bacteria within it as the flames. It’s important to get calves eating solid feed ASAP to stimulate bacterial fermentation and the development of the rumen lining and the rumination reflex:

- Coarse tasty concentrate/grain mixes available from birth. Change daily to keep it fresh and clean.

- Good quality high protein hay (but not so much that it limits concentrate intakes).

- Clean water should always be freely available

Feeding more milk

Another thing to consider in cold weather is to increase the amount of milk that calves are fed. For example in the USA (where things get much colder than here!) they may increase:

- Milk volume: from feeding 3L twice a day to 4L twice a day

- Total solids of the milk: continue at 3L twice a day but increase the total solids from 12.5% to 15%

- Frequency: from feeding 3L twice daily to 3L three times a day

Make any feed change gradually as rapid changes in volume or total solids can upset the calf’s intestinal bacteria and on occasion lead to outbreaks of Salmonella. Sudden increases in total solids when mixing milk replacer (either in water or milk) is where we see this issue most commonly.